COSTUME DETAILS FOR WRITERS–MEN IN 1910s

Men’s clothes have not changed as dramatically as women’s clothes over the past century. Here’s the scoop on the variations for the decade of the 1910’s.

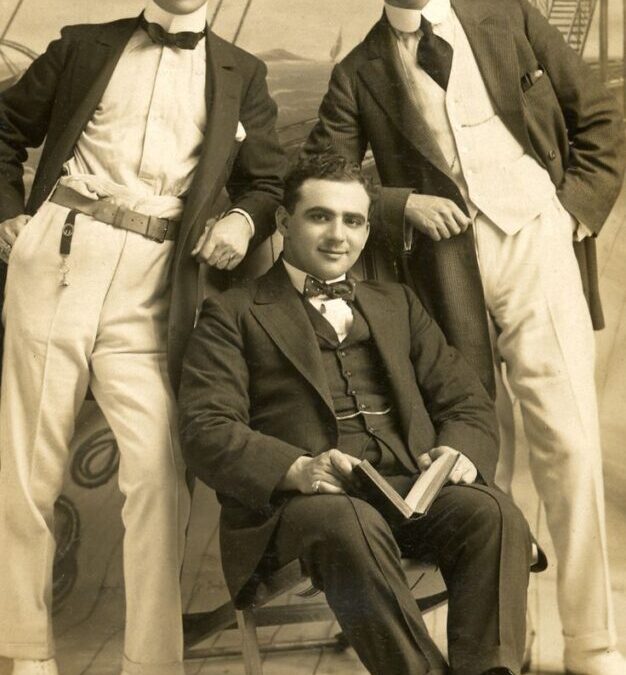

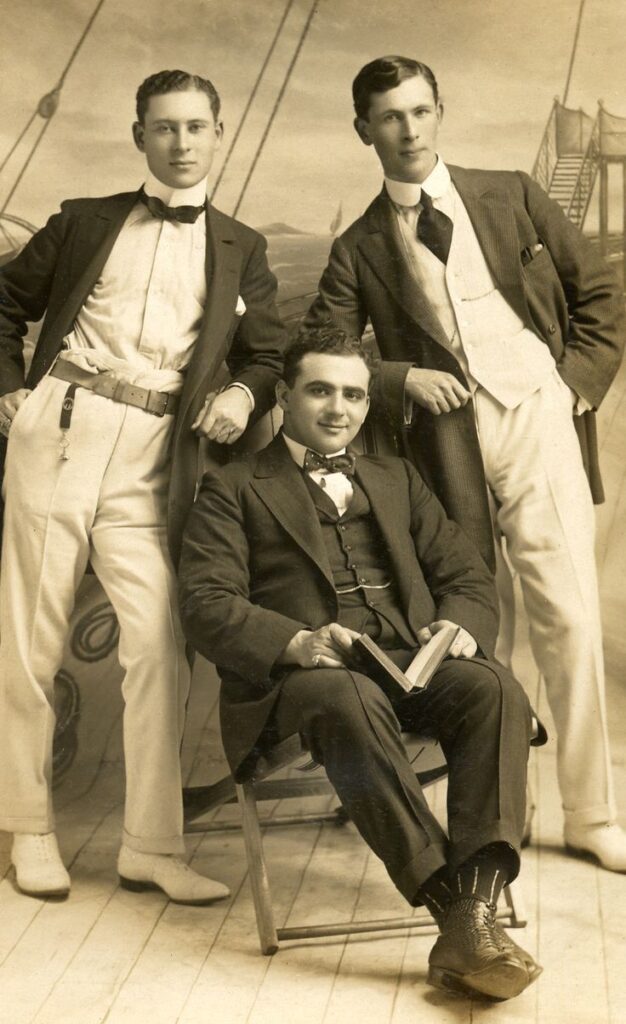

Hairstyles were modified pompadours in the early years of the decade. As the war rolled around, and then the boys came home, they started sporting more easy-care hairdos, short, slicked back, or to the side. Whiskers and mustaches were still seen in 1910. But as the years continued, the young men started emulating the military requirements and facial hair generally disappeared among them. Older men clung to their older styles. So, if your young hero just returned from the Front, he isn’t going to be twirling his long mustache.

Among businessmen and professionals, the suit was the choice for day wear. They were called sack suits, even in the ads, the reason being that they were baggy. The early years of the decade, the sack suits consisted in a long, plain loose-fitting jacket, 30-32” long. This made them end at mid-thigh. The lapels were a standard 2.75” wide. There were 1-3 buttons. The winter colors were dull, dark navy, grey, green or brown. Any striping, checks or plaids were hints, rather than obvious. Summer colors were light grey, tan and off white. The jacket edges were straight edges or slightly rounded at corners. The pants for the suits were high-waisted with straight legs sporting a crease both front and back. They were cuffed at the ankle. Suspenders, either elastic or leather, were used to hold them up. Belts were used for sporty clothes, only. Suits were accompanied by collarless vests with 6 buttons. Before the war, the vest was cut low enough so that it was not seen when the jacket was buttoned. After 1914, the vests took on more prestige and were cut higher.

After the war, the young men returned with their own tastes. The material was more colorful, the look more tailored with a defined waist. Shoulder pads were gone, the jacket hem moved up to mid-hip and showed off large patch pockets. Materials were lighter. The extreme version was called the jazz suit. It had tight shoulders and waist with three closely placed buttons. The pant legs ended above the ankle. It was a strange name to give the suit, seeing as it was too tight to dance in. The materials changed too, making the suits lighter in weight. Light wool was not the only choice. A new cloth had been developed called Palm Beach cloth. It was a tropical weight mohair-cotton blend which was washable and comfortable to wear. The suits came in cheerful colors like lilac and sky blue, checks, windowpane and stripes.

Like today, men wore dress shirts with their suits. These shirts were in pale colors or stripes. Detachable collars were coming in celluloid, for high stand versions. Attached collars came in pointed and round versions.

Coats were more popular then, than now, probably because there were no such thing as heated cars, yet. Every gentleman had a coat, or three. One of the most renowned coats of the era was the duster. Designed for driving in a dusty open car, these coats were popular with the young men. Ankle length, with side buttons, they came in gabardine, twill, duck and Palm Beach cloth. They were either white, light tan or lemon.

The heavy coats for gentlemen came in several different styles, all wool, all knee-length or longer. They were made of wool, melton or chinchilla weave, and lined with heavy cloth or fur for warmth. The Chesterfield was a plain coat with a velvet collar, looking very gentile. The ulsterette had a cape over the long sleeves, narrow lapels and collar. It could be made with lighter material, too. The Inverness cape coat was similar to the previous, but without sleeves. The suit coat sleeves were shown below the caped shoulder. Some materials could be rubberized for rain protection, or oil cloth could be used.

Working men had to have specialized work jackets. Some jobs were outdoors. Oiled or waxed cotton coats and pants worked for rain gear. For warmth, there was a reversible leather and corduroy double-breasted jacket fit to just below the hip. There was also a sheepskin-lined corduroy or moleskin jacket which could be waist-length to knee length. The well-known Indian blanket plain mackinaw was very popular and has continued to be so to this day. The reefer coat (now known as the pea coat) was longer and, thus, warmer, than the jackets.

Footwear was of three types: boots, business dress shoes and pumps (yes, that is what they were called for men). Boots, used for travel, business and labor, were a few inches above the ankle. They were usually attached by a combination of laces and hooks. Some were two tone. Heels were not flat like typical boots today, but had a height of 1 ½”. For business, men could also wear shoes, cut high on the foot, mostly single tones like brown, black patent leather, gunmetal or white. They were very plain, with broguing (cut out patterns) for country wear only. The heels were 1 – 1 1/2” high. Formal pumps did, indeed, look similar to women’s pumps today, cut very low with a heel from 1 – 2” high. Laces were made of ½’ wide silk with metal covered tips, which tended to rust.

Accessories were common among men at the time. Pocket watches were very obvious until 1914, worn in a vest pocket with a chain that fit into a button hole. Then wrist watches came out. As is typical, the young men wore them first. All gentlemen wore gloves. Leather and suede were most common in the winter, cotton in the summer. The colors could be white, grey, tan or matching the neckwear.

The type of neckwear worn depended on the time of day. Cravats or large bow ties were for daytime. Narrow bow ties were for evening wear. Dark long neckties showed around 1914.

Socks were mostly black or grey wool. They were valued as difficult to produce, so they were cared for and mended as needed. Dress socks for the wealthy were cashmere, sild or cotton and might be embroidered. Being as there was no elastic in socks, men had to worry about them bagging around the ankle. So, they had elastic or leather sock garters at the upper calf where the socks were attached. Those who did not have much, like workmen, had drawstring cords at the top of their socks to tighten around the calf.

The hats of the Edwardian age, the derby the top hat and the homburg, were mostly gone after the war. The young men coming home from the war wanted color, not black and brown. They chose the fedora, with its grosgrain ribbon, flat caps in many colors, or straw hats, like boaters. The Panama hat, a new kind of weave, though expensive, was very popular.

The men looked good throughout this decade.

Recent Comments