RADIO ENTERTAINMENT OF THE 1930s/

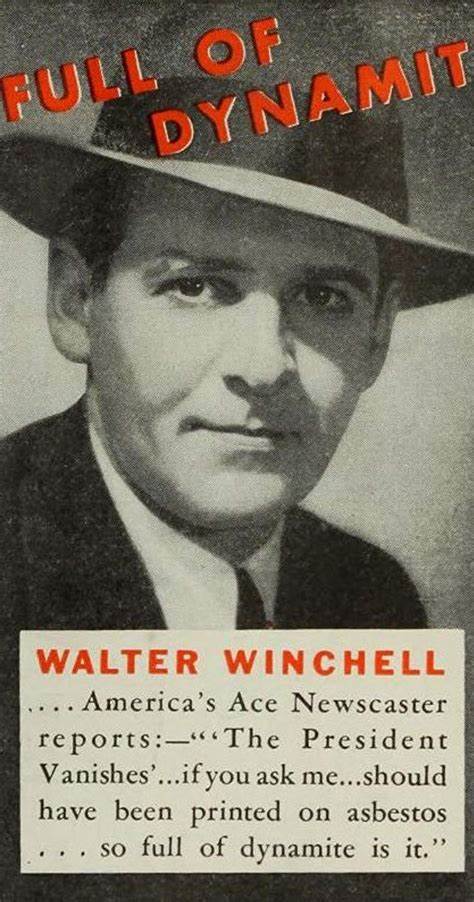

Walter Winchell

In my book, The Matter of a Missing Stutz, a Harvard professor and his wife are so intent on listening to the radio broadcast of Walter Winchell, that they don’t hear their new car being stolen. Who was this Mr. Winchell and why did his radio broadcast mean so much to them that they didn’t even hear the engine of the car start?

The 1920s and 1930s were a time of complete cultural change. Dresses moved from ankle-length to just below knee. Men’s faces became hairless. Newspaper publishing was at its peak, but soon to give way to national broadcasts 24 hours a day. Pianos in every home became silent as the radio music filled the houses. And house parties played second fiddle to the movie matinee.

Electronic entertainment was thrilling. There was something new every few hours all day long. Parlor seating was rearranged to get in close to the entertainment center. That was a radio. In the years before the war, this usually meant a furniture sized cabinet with speakers built in and three knobs prominently placed. One was the on/off switch. One was the volume switch and one was the channel changer, sitting below a window showing where on the dial you were tuned to.

Shows were anywhere from 15 minutes to 30 minutes in length, including the commercials. For anyone who could afford a radio, there were a variety of shows. Comedy, drama, crime stories, gossip (all the dirt on your favorite politicians and actors!) and news commentary vied with orchestras for attention. And the attention was not only for the actors and actresses but also for their sponsors (nothing has changed in 100 years!) The sponsors of many of these broadcasts were companies who sold every day household items, soaps, cold creams, cigarettes and, later, food products.

Walter Winchell was different. He didn’t have a show, he had a following. In the 20s, his newspaper column was read by 50 million a day. He worked for several radio stations, starting with CBS in 1930. He did a 15- minute business analysis and gossip of Broadway and moved to another radio station in 1932 where the same information was sponsored by Jergen’s. These shows went national as people were entertained by his innovative style of gossipy staccato news briefs, jokes and Jazz-Age slang.

By the middle of the decade, Winchell had seen enough of the underside of crime, reporting on the activities of the criminals, who also happened to be his friends. It got dangerous for him. So, he switched sides and started rooting for J. Edgar Hoover and his crime-solving capacity. Soon enough, he started to see how Hitler was destroying Europe and joined that bandwagon to condemn Germany and the isolationists of America. Being Jewish, himself, this disaster was dear to his heart. During the war, he supported the president and insulted the president’s enemies.

Later, he claimed he could speak at 200 words a minute, delivering the news so quickly, that people had to pay very strict attention. With the quality of the transmissions being what they were 80 years ago, and his voice being the unique type that it was, we can assume that the professor and his wife would not have been able to concentrate on Mr. Winchell’s news and the neighborhood noises at the same time.

Recent Comments