Many of the women in this series are virtually unknown to the public. These women were just living their lives. They did not see themselves as exceptional. We do. Our first woman in American history is Verlinda Graves Stone:

Verlinda was the middle child and first daughter of Thomas and Katherine Crowshaw Graves, born about 1618. Thomas was a young man of some money and an adventurous spirit. He bought two shares in the new Virginia Company in 1607. This entitled him to a trip to the wilderness known as Virginia. Thomas came over, a single young man of about 21, in 1608 on the

Mary and Margaret. He participated in the development of Jamestown, while, at the same time, going back to England every few years. While there, he married Katherine Crowshaw and had all his children there. They moved to the East coast of Virginia over time, the last coming over by about 1630. The children were: John, Thomas, Verlinda, Elizabeth Ann and Kathryn.

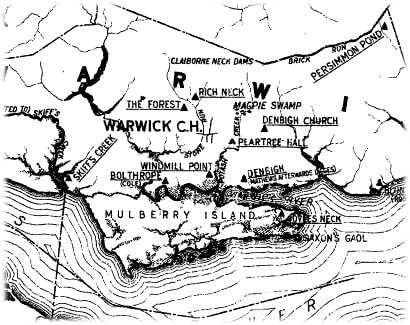

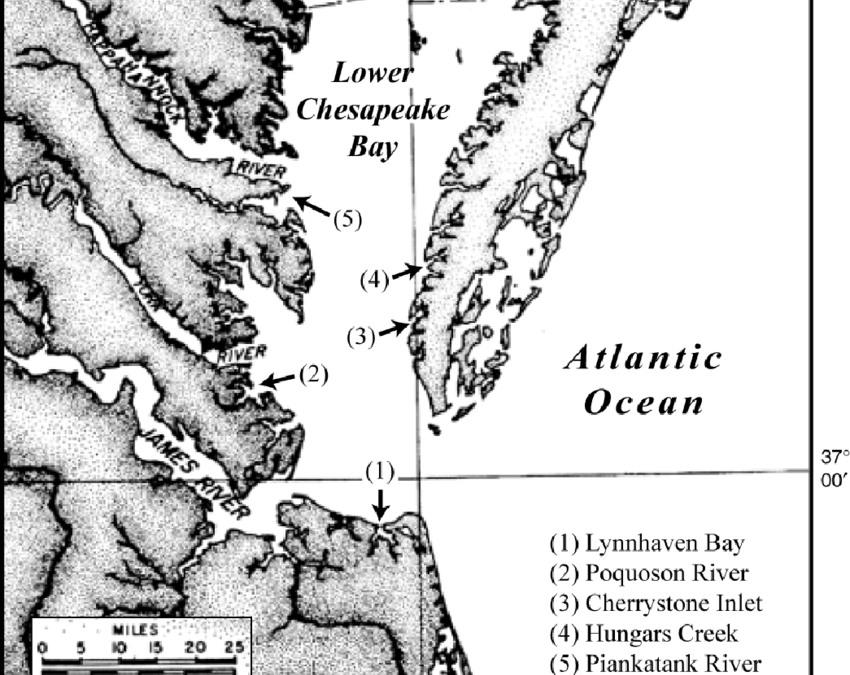

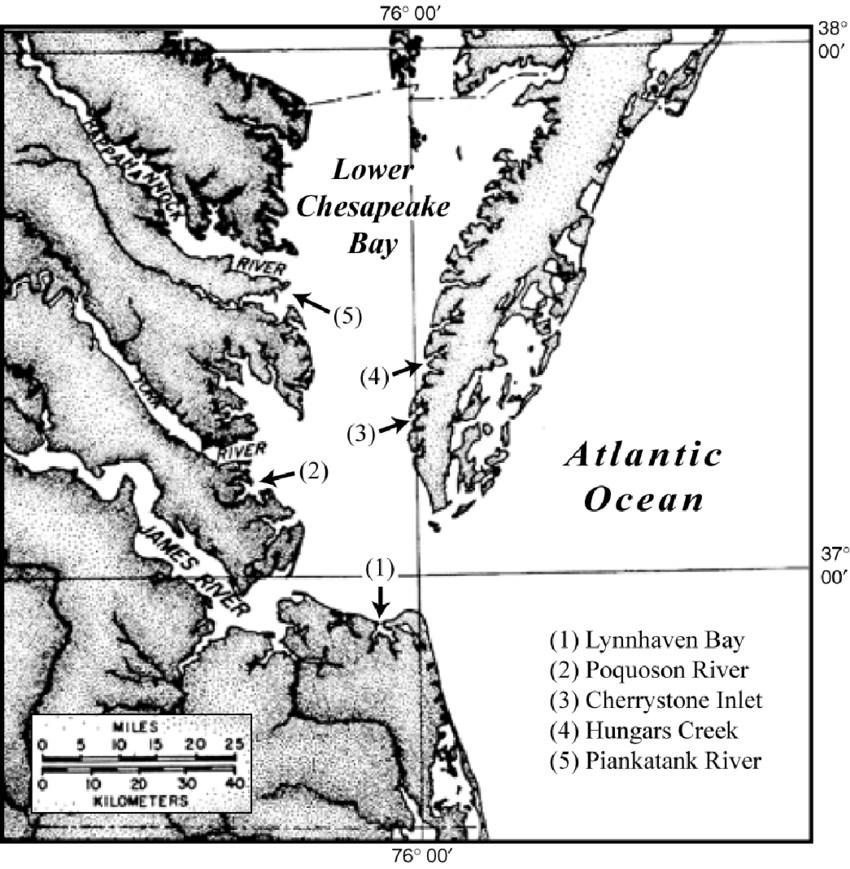

In an era where girls were married off in their mid-teens, Verlinda married William Maximillian Stone, a man 15 years her senior in either 1634 or 35. Stone had been in the colony at least 6 years and had developed, with his brother, John, a prosperous trading business. He had a plantation on Hungar’s Creek, where he had built a comfortable house.

Verlinda, aged 16 or 17, became the mistress of a very active plantation, which grew rapidly. Within 12 years, the couple had nine servants, and acquired twelve more, with time. The plantation was sizeable and grew tobacco, corn and other foodstuffs. Stone was very busy with his merchantile business. In addition to that, he was sheriff, member of the House of Burgesses or vestryman for the next thirteen years.

This meant that the young wife was not only obligated to raise the children (they had seven between 1638 and 1655) and direct the servants, she was also obligated to hostess monthly county court or monthly vestry meetings. Without hotels or motels in existence, she probably hosted more than her share of visiting business partners. Verlinda was an active member of the dinner conversations, which were probably mostly business and politics in nature.

As the English Civil Wars began, politicians were split along religious lines, with the Cavaliers supporting the king, and the Anglican Church, and the Parliamentarians supporting the Puritans. The arguments spilled over into the colonies, especially Virginia, where Governor Berkeley demanded a strict following of the official English faith. The East coast, accessible only by crossing the Chesapeake, was not touched much by Berkeley’s insistence until the mid-1640s. More Puritans had moved to the small peninsula and their voices were being heard.

Meanwhile, Leonard Calvert, the proprietary governor of Maryland, had difficulty attracting new settlers to the new colony. In 1643, he returned for a visit to England and had George Brent be his stand in. The Stones were already thinking of moving to Maryland by then. It appears they chose to occupy part of the land owned by Calvert as early as 1645. It was a 100 acre tobacco plantation with a large house. St. Mary’s City, the capital at the time, is bordered by the

St. Mary’s River, a short, brackish water tidal tributary of the

Potomac River, near where it empties into the Chesapeake.

Calvert returned in 1645 and died of an illness in 1647, leaving Maryland without a governor and his two little children without a father. His brother, Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, was the general governor of the colony, and had to find a new governor. Knowing the story of William Stone, Baltimore asked Stone to become the third governor and first Protestant governor of the colony. Verlinda moved her little children, probably only three so far, her nine servants and a household of furnishings to St. Mary’s.

The family bought Leonard Calvert’s house, sold to them by Margaret Brent, the executor of Calvert’s will. It was a much grander house than the one the Stones had in the largely unsettled area of East Coast Virginia, a home built for the younger son of a baron. This became a problem some years later.

Here, again, Verlinda played hostess to businessmen and politicians. There was no meeting house for the assembly, so they stayed and had their meetings at the Stone’s house.

In April, the general assembly met with the purpose of discussing sixteen bills. This included an Act Concerning Religion, a guarantee of religious freedom to all Christians. The bickering and shouting, as well as the large amounts of alcohol required to quell the thirst of the politicians, required a woman of amazing patience.

After the first few years of relative calm, the anxiety of the civil wars in England entered the everyday life of Marylanders. In 1652, Stone was deposed and lowered to the level of governor’s council. But, after a short time, he was reinstated. This did not last long. In 1654, Parliamentarian representatives came to Maryland and took over the government. Verlinda, William and the children were obligated to go into exile in Virginia. Within months, Lord Baltimore persuaded William to go back to Maryland, with supporters, and defend the colony against the Parliamentarians.

With a band of only 100 followers, William went 75 miles north of St. Mary’s City to the Severn River, where the town of Providence, now Annapolis, had been founded only a few years before. There he engaged the vastly over-numbered Parliamentarian troops. Half his men were killed or maimed and William was injured badly, his shoulder damaged. It was obvious that he needed to surrender. And once he did, he was taken prisoner. Verlinda, having stayed behind in safety, was not.

Hearing of the treatment William endured, Verlinda went to nurse him. On her arrival, she immediately wrote a letter to Lord Baltimore giving details of the enemy and requesting aid at once. The letter showed Verlinda to be a well-educated, well-spoken woman with great powers of analysis. Baltimore probably did not do too much for them, for the letter would have hardly had time to reach him.

Many of the soldiers Stone fought against were the Protestant emigrees from Virginia whom Stone had invited to move to Maryland. When he was sentenced to being shot to death, a number of the soldiers objected. He was subsequently released a month later. He resumed his position as governor for a few more years. His retirement ended William Stone’s public career.

At the end of the decade, when King Charles II ascended to the throne, Lord Baltimore offered the Stones a tract of land in Maryland, as large as one could ride around on horseback in a day. They thus acquired land in Nanjemoy, 60 miles up the Potomac. They named the plantation Poynton Manor, after the place William’s family had in England. William lived there, developing the manor, and died at the end of 1660.

The new widow lived in St. Mary’s City for a while but a few years after William’s death, the son of Leonard Calvert, William, sued her for trespass, claiming she had no right to Governor’s Field. The son of the old governor claimed Margaret Brent had no right to sell the house, which they had closed on in 1650. Despite a court battle, Verlinda lost her plea and moved to Poynton full time. The odd thing is that Verlinda’s oldest daughter, Elizabeth, eventually married the young William Calvert and would have had access to the house, had it not been sold to the colony as a meeting house for the assembly.

Verlinda lived at the manor during her widowhood, per her husband’s will. However, she acquired land in her own right, purchasing 300 acres in Charles County in 1664, which she named Virlinda. Two years later, she acquired 500 acres in Prince George County.

When Verlinda died, July 13, 1675, she was considered quite rich, being worth nearly 15,000 pounds of tobacco.

Recent Comments