Frances Grenville

FRANCES GRENVILLE WEST PEIRSEY MATHEWS

Frances Greville was the daughter of Giles Grenville and born around 1598-1600. Frances appears to have been the oldest of seven or eight, and the only girl. She grew up in Charlton Kings, about 25 miles from the bustling city of Bristol. One can assume that Frances grew up in a middle class environment, but, reading between the lines, it seems that her family was probably the “poor” side of the family.

One of Frances’ distant cousins was Mary Conroy, the daughter of Elenor Grenville . Mary was 20 years older than Frances, so they probably were not close. Around 1601, Mary married William Tracy. Tracy had many associates who had invested in the Virginia Company, specifically, the Berkeley Hundred plantation, including his cousin, Richard Berkeley. Tracy became involved with that investment. A multi-talented man, Tracy was also a ship’s captain. In 1620, he was captain of the ship Supply. In September of 1620, the ship left Bristol with fifty passengers, and four times as much alcohol as would be expected to be used on the trip, to Virginia. Most of these people were expected to work on the Berkeley plantation. Tracy brought his wife, Mary, their children Judy and Thomas and Mary’s cousin, Frances, as well as three maid servants. The ship landed in early 1621.

It appears that the quite famous Wests, the father being the second Baron DeLaWare, and the Grenville grandfather were close friends. Some sources say that Nathaniel West, the baron’s youngest son, had been promised the hand of Frances. One view is that taking her to Virginia was simply to marry her to West. Of all the West brothers, and there were twelve children, three had plantations near Jamestown. This was perfect, from the point of view of Mary, who would be Frances’ chaperone. Westover plantation, Nathaniel’s place, was only a mile from Berkeley plantation. Within months, Frances and Nathaniel were married. Judy also married almost immediately. By April, 1621, Captain Tracy was dead. Thomas and Mary returned to England, leaving Frances alone with a new husband in a new world. Unfortunately, Judy and her husband were killed in the Indian Massacre of March 1622.

Frances’ marriage did not last very long. Nathaniel died somewhere between April 1623 and February 1624. They had a two-year-old, Nathaniel, Jr. Right after West’s death, Frances moved into the home of her brother-in-law, Francis, where she was living at the time of the census in 1624.

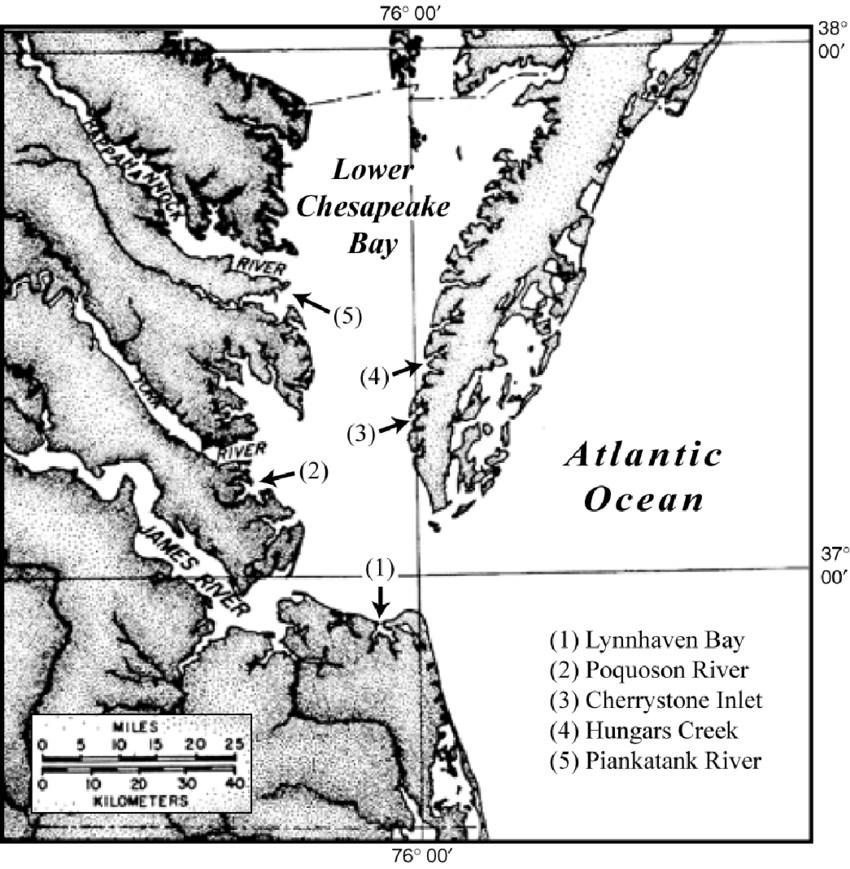

A beautiful young lady of probably only 24 or 25, Frances attracted the eye of Abraham Peirsey. He was one of the richest men in Jamestown, a widower with two teenaged daughters. Marrying Frances gave him control over Westover, the plantation that Frances’ baby had inherited. Peirsey had bought the large, well-endowed Flowerdew Plantation, across the river, a year before Frances and he married. It had belonged to George Yeardley, the governor, who planned on moving back to England after his tenure was up. Unfortunately, he died before that. This purchase made the Peirseys the largest landowners in the colony. They renamed it Peirsey’s Hundred and Abraham had a large stone house built to replace the smaller house on the premises. This marriage gave Frances a step-father for little Nathaniel and almost anything material she could want. However, Abraham died 16 January of 1628, at only 41. In his will, he made Frances the executrix, with orders to sell the plantation for the best price possible. He meant to have the two daughters inherit the proceeds.

Frances did not sell the land. She married again, within a year, to Captain Samuel Mathew. As a widow, she was now probably the richest woman in the colony, with two large plantations, very attractive to a prospective groom. The captain was probably the richest man in the colony. He was an attractive catch.

Frances and Samuel kept the Hundred to use as they wished, along with Westover, which belonged to her son, and Mathew’s plantation, Mathew’s Manor, later renamed Denbeigh Manor. There was much of value at Peirsey’s Hundred, not just the land. Apparently, the couple and their servants moved much of value, including Peirsey servants, to Mathew’s Manor, downriver on the north side of the James. The Hundred was not maintained well for several years while Frances and Samuel concentrated on building their family. Samuel Jr. was born in 1629/30 and Francis in 1632. Although Frances could have anything, being so rich, she could not have her health. In the end, she was dead before 1633 was over, leaving Samuel with two very little boys.

Nathaniel Jr. eventually moved back to England. His uncles watched over him carefully and guided his education. One uncle, John West, was governor for a short period after the “thrusting out” of Governor John Harvey in 1635.

Frances and Samuel’s lack of action on the Peirsey plantation lead to much hard feelings between Mathews and the orphaned daughters by 1634. Both young ladies were now married and filed suit against Mathews for possession of the plantation and all the goods which had been there. The suit was eventually dropped but not before the governor gave the sisters permission to have their agents ransack Mathew’s Manor. Mathews and his family were in London at the time, charged with treason. It was easy for the sisters to retrieve their father’s furnishings and goods.

It appears that Mathews married again, fairly soon after the death of Frances, so that his two boys would have a mother. They were raised by Sarah Hinton Mathews.

Recent Comments